Domestication

One reason that learning the language of needs is not so easy as it might be is that we actually already know it. This was our first language, in fact. As little children we sensed instinctively how important our needs were and we came into this world totally present with our feelings. Actually, we had no other language than Needs-based Communication. We told our parents and carers what we felt and what we needed with body movements, facial expressions, and whatever sounds we could make.

As infants, if we were reasonably lucky, our parents and carers listened to our expressions of our needs and met them as well as they could. By and large, in the absence of outright neglect, our ‘language’ of feelings and needs worked, in the pre-verbal stage at least. We got fed, and changed, and held. The trouble started when we began to learn to speak. We learnt our language from those around us, and they of course were not talking about their needs and feelings. They were naming objects and comparing them, they were telling us over and over what was good and bad, right and wrong; they were criticising and complaining and using language to manipulate and co-erce us, whether persuading us to eat more carrot slop when we were not hungry for carrot slop or getting us strapped into the straight jacket of a car seat when we actually wanted to play with the cat. So we also used our language skills to please our carers by naming and comparing objects, for example, and were immediately rewarded by our proud parents for any successes in that field. With our emerging ‘ego’ identities, we used language to claim exclusive rights of ownership over objects in our environment, and got reinforced for that as well – “That’s Emma’s toy, Jimmy, let her have it!”; flushed with success, we expanded to making general demands and complaints and for all the other unfortunate reasons we saw everyone else using the gift of language.

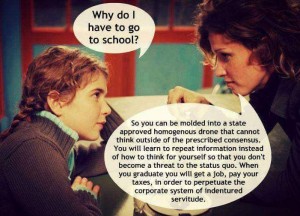

Meanwhile, perhaps as we started getting more independence of movement, our carers didn’t seem to be quite so ready to listen for and to interpret our needs. There were other mouths to feed, maybe, and other stuff to take care of in our parents’ busy lives. Toddlers are still pretty good at telling you when they’re hungry or tired or wanting comfort or excitement and so on, but around school age, if not before, they learn that it’s only their immediate survival needs which are likely to be taken seriously. Anything else is likely to have to give way to the demands placed on their time and freedom by the daily schedule and limitations of the home environment, as determined by the adults. We keep on for a while asking for what we need, perhaps in an ever more plaintive tone, wistfully remembering the good old days when we only had to look someone in the eye to get that instant beaming smile of love and appreciation, but after we’ve heard a few hundred times, “Not now Johnny, I’m busy..“, or “No you can’t have pudding until you’ve eaten your vegetables” or “If you ask me again you’ll go to your room!“, etc, we learn to ‘stop pestering’ and we resort to the tactics we see the adults around us using: where possible we simply take by superior force, and where not, we wheedle, lie, trick, manipulate and ingratiate ourselves in order to get what we want. Since nobody sees our needs anyway, we increasingly do like the grown-ups, and focus on wants and strategies instead. We insist on specific foods (or sweets) when we are merely hungry, demand the latest PlayStation or X-box when we actually just want to play a fun game, and whine if we can’t stay up late to watch TV, when all we really crave is to be included in what the adults are doing.

All of us have been ‘domesticated’ like this, and in the process we’ve learnt that our needs are not important and our feelings are best kept to ourselves. We’ve been told countless times that it’s not OK to get angry or tearful, that we shouldn’t argue or jump up and down or walk slowly or run or stare or ask awkward questions or talk to strangers or enjoy our own bodies… and a million other do’s and don’ts and should’s and shouldn’ts. Our feelings and physical desires have been suppressed, our energies have been channelled into ‘acceptable’ activities, and we have been bullied and manipulated into trying instead to meet the needs of our siblings, parents and teachers. We have, as they say, been ‘taught wrong from right’. Alas! We have learnt the language of the world, labelling, comparing and judging not just the qualities of inanimate objects but the moral value of every person and action, according to whatever arbitrary standards prevail in our social environment. By the time we reach adolescence, it’s become hard for us to construct a single sentence without saying that one thing is ‘good’ and another is ‘bad’ (or whatever the current terminology is!) – whether it’s pizza toppings and pop music or the other kids in our class we’re talking about. Our heads are already so full of received beliefs, fixed opinions, assumptions and generalisations that we can hardly think for ourselves, but that troubles us little as the skill our society prizes most highly, whether in TV talent contests, academic studies, politics or the justice system, seems to be the ability to criticise, judge and belittle others. Meanwhile the values our parents and teachers want us to cultivate, especially if we have siblings, are a confusing blend of self-sacrifice at home and self-promotion in the outside world. We begin to lose contact with our own true needs and our own selves, and by extension we also lose any meaningful connection with other people and real sense of caring for their needs.

All of us have been ‘domesticated’ like this, and in the process we’ve learnt that our needs are not important and our feelings are best kept to ourselves. We’ve been told countless times that it’s not OK to get angry or tearful, that we shouldn’t argue or jump up and down or walk slowly or run or stare or ask awkward questions or talk to strangers or enjoy our own bodies… and a million other do’s and don’ts and should’s and shouldn’ts. Our feelings and physical desires have been suppressed, our energies have been channelled into ‘acceptable’ activities, and we have been bullied and manipulated into trying instead to meet the needs of our siblings, parents and teachers. We have, as they say, been ‘taught wrong from right’. Alas! We have learnt the language of the world, labelling, comparing and judging not just the qualities of inanimate objects but the moral value of every person and action, according to whatever arbitrary standards prevail in our social environment. By the time we reach adolescence, it’s become hard for us to construct a single sentence without saying that one thing is ‘good’ and another is ‘bad’ (or whatever the current terminology is!) – whether it’s pizza toppings and pop music or the other kids in our class we’re talking about. Our heads are already so full of received beliefs, fixed opinions, assumptions and generalisations that we can hardly think for ourselves, but that troubles us little as the skill our society prizes most highly, whether in TV talent contests, academic studies, politics or the justice system, seems to be the ability to criticise, judge and belittle others. Meanwhile the values our parents and teachers want us to cultivate, especially if we have siblings, are a confusing blend of self-sacrifice at home and self-promotion in the outside world. We begin to lose contact with our own true needs and our own selves, and by extension we also lose any meaningful connection with other people and real sense of caring for their needs.

Is it any wonder that we now struggle, having encountered again this very different way of thinking and speaking which NVC offers, to go back in our adult bodies to the infant’s world, where our needs were ever present – and often respected? A thousand voices are crying within us that this can never work, that people will laugh at us or criticise us, that we shouldn’t be ‘needy’, that we should think of others first, that life in the real world doesn’t work like this, and so on. The whole process of ‘growing up’ has trained us to believe that considering one’s own needs is selfish, that relationships are not about meeting one’s own and each other’s needs voluntarily, but about compromising, that we shouldn’t say what we mean but what people want to hear (“Say ‘thank you’ to grandma!“), and so on.

Reversing such a long and thorough training, which started when we were most impressionable and willing to learn, cannot be an overnight process. Unpicking the stories of separation, letting go of the deeply indoctrinated urge to compete with and defeat our ‘enemies’ while sacrificing our own truth, takes time, patience, conscious effort and support. Usually the process of healing and reframing also requires mourning: connecting with the pain of the needs unmet for so many years, and releasing it with forgiveness for those we might blame for what we went through. They too were domesticated into a dysfunctional human society and have their own journey to go on. But it can stop with us if we choose.